[fiction]

He saw me as soon as I parted the doorway’s winter curtains to enter the club.

I wished that I had a cellphone I could have used on the spot. I thought about immediately turning around to leave and go tell Ana, but that would give him too much recognition he didn’t deserve, or that he’d internalise as another small victory after the shit he’d caused this past week.

I was stopped and stood in the queue to pay the Saturday night band’s small cover charge. Got the back of my right hand stamped. Hadn’t thought of it earlier but I was dressed like an acorn from one of the local oak trees: long green body with an orange cap. Cold enough a night for headgear and a ball cap just wouldn’t do. Hunter orange toque covered my ears well on the bike ride into town. Almost wished that I had worn gloves.

He was diagonally across the club from the entrance, sitting on a stool at the one high table in the almost empty joint, watching in what looked like a medicated sloth slouch with a strange expression on his face. A sloppy, drunken grin. An “I’m too high, having fun. I’m about to hit my stride. Watch me. Watch me! You ain’t seen nuthin’ yet!” look. His cigarette arm made long, slow sweeps, or arcs from his mouth down across the square table until his hand hung over the edge, and stayed that way long moments until the cigarette’s ashes fell to the floor of their own accord. Watching him was like watching a television program’s slow-motion film footage of an animal marking territory in the woods—making claw marks, or signs on trees and exposed rocks—without the voice over.

It wasn’t my usual place in the club but I went to the left end or side of the bar, beside the stairs leading up to the Turkish toilets, kitchen and dining area. Wasn’t going to go to the right side with him there alone, looking as if he was presiding over the dance floor. Didn’t want to talk to him, but knew that even to avoid him would acknowledge him. I wanted to pound him.

Two women were doing soundcheck vocals on the slightly raised stage: “voulez-vous coucher avec moi, ce soir?” over and over again. They at least had the words well in hand. One of the women had short reddish hair like Bobana’s. The other woman’s hair was long, dark, thick, and looked to have come from an early ’60s beach movie. Man with a saxophone went next: blowing and leaning backwards with the instrument’s brass mouth pointed at the ceiling well behind him until the clear sound cracked too loud.

I took off the green jacket and stuffed it a cargo pant’s pocket. Took off the brown sweater and tied it around my waist. Better there than hung on a wall hook behind people I didn’t know. Stood at the bar in a small cone of light and ordered a bottle of my usual deer beer, poured half a glass, and took my first sip of the cold, golden lager.

Then I waited.

Woke up with Murphy and an incident without conflict resolution from many years before in my head. Had the stress, the panic on high but the story stopped in that moment of highest tension. Any conclusion would have been a wakeful attempt to appease my inabilities in real life.

A neighbour’s dog barked as the metal gate on the street rattled while being unlocked. Minutes later, their kitten yowled at one of my doors or windows. It must have slipped out when whomever entered and let the dog inside the main house. That person climbed the stairs and entered the bathroom above my room. Ah! The refreshing sound of a man peeing into water: must be Matthew or his son, Alex. Nice! Very dark outside. It was definitely before dawn, but with the weekend’s falling backwards of time on clocks I couldn’t hazzard a guess. I would have to find my watch on the chair beside the bed, or get up and turn on a light. Going to the bathroom myself might not be a bad idea...if it helps me fall back asleep...or...

My sister’s head disappeared into the backseat of the taxi. She drove off with Mark for dinner downtown at La Fenętre before they went to the ballet. It was Nutcracker season again. Even though I had managed with her help to get a visa and had travelled all that impossible distance to visit her, she had so many other things to do, so many people to see, without me.

I turned back to the half open EXIT ONLY door of the gym club, wondering how, in this cold rain with slippery leaves on the streets, I was going to safely get her motorbike and Dilbert the New Zealand sheepdog and her gym bag to her apartment. I wasn’t the most experienced of drivers, and definitely not in this city, this country.

At the payment window I asked what the charge for today was, as I didn’t want my sister’s account to be charged for me.

“Workout, private game room rental, juice bar...that’ll be forty-four fifty.”

Dilbert started barking. I turned around to find some meathead untying Dilbert’s leash from the ironwork grill of the window.

He turned and growled at me, “You can’t have dogs in here. Our founder, Murphy, was mauled by a dog.”

I replied as I reached for the leash and the bags, “That dog has been coming here for years. It’s my sister’s. I’ve seen pictures of it eating out of Murphy’s hand.”

He jabbed me and said, “You can’t have dogs here. I’m telling...”

I pushed. I pushed him into to the potted plants—orange trees and big jungle leaf things—recovered Dilbert, and said, “Leave us alone, if you want to enjoy the rest of your days at Murphy’s Gym.”

Another meathead tried to grab me while saying, “You can’t...

“Back off! If you know what’s good for you. Murphy knows my sister. You don’t know me. You don’t want to know me.

Capiche?” I said, while seeing more people converge on us. Had to get Dilbert and me out the door without buddy in the shrubbery, buddy in my face, or anyone else wanting to restrain, or pound on us...

Since then, I’ve heard other stories about Murphy: How he’d been an air cav pilot shot down in flames in the first Gulf War. That he’d been awarded medals and has played golf with the President. Or that his best-selling autobiography didn’t tell the truth...but what’s the truth when one person, or their ghostwriter, sets out to tell the tale of a life lived? That he’d been running drugs when shot down by so-called friendly fire. That his several mansions were filled with beautiful women lounging beside pools. That in revenge for his face, he killed dogs with his bare hands. That he was incapable of sex. That he watched others kill dogs for pleasure. That he has at least a dozen children in five countries. That his global gym, or health and fitness training empire was worth over a billion. That the operation was really a front for the mob, or for a government agency...

The back neighbour’s light has come on. Their door opens and their little mop dog is let out. It’s garbage day. Someone at the neighbours’ house on the right must also be up. Through the closed window comes the sound of a corn broom sweeping the night’s fallen leaves from their walkway and steps. Get it done now and it should still look perfect when today arrives in half an hour or so. It’s time for the early birds to go to the farmer’s market and bakery.

Not me. It’s not market time for me. Even here market needs money, or something to barter. Being alive, even doing things, doesn’t mean one has or gets money. Today, I’ve just a few words to mix together and some up with something better than an apology for Friday.

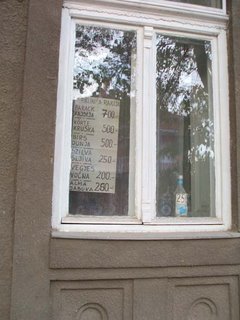

I could be camped out in a field in a simple A-frame of grass or corn stalks on poles, a flock of sheep in my care. Small fire inside a circle of stones for the pot of boiled water for my one cup of coffee today. Chunks of kobasica and cheese in one coat pocket. The end of Saturday’s bread loaf in another. Tobacco and papers to fill my day. A small bottle of plum brandy to ward off the night.

Grey overcast sky this morning. Brighter than yesterday morning before the showers arrived. Off in the distance, the highway between not-here places is filled with transport trucks, buses and cars. They flow faster that any river around here and are far louder than the lazy, winding rivers, but I can watch them the same way.

Overhead, I sometimes see the trails of aeroplanes, but not today. On sunny days, I will sometimes see the light reflecting off their shiny bodies. It its shadow passes over the sheep and me, I shudder. It’s absurd to think there’s so many people buckled into seats up there going somewhere so far away that they need to be nine kilometres above the earth just to get there.

Occasionally, a pair of fighter jets roars low overhead, or a dark green helicopter with a propeller in a hole in its tail patrolling above the highway veers away and comes closer to check me out. I don’t change position to stand up and look or wave. I stay in my sitting on my heels crouch, lit cigarette in the fingers of my left hand, eyes on my sheep and the dog on the far side. Just another shepherd in bulky nondescript brownish coat. That’s me.

Only a few years ago, a decade or so, I was on the wrong side in the hills. We were all on the wrong side when the Americans came with bombs to stop the fighting. Sometimes, I shot at helicopters overhead. I shot at trucks. I shot at lights on the other side of the valley at night. I shot at movement or lights below if they weren’t ours. Am certain that sometimes I got someone, likely even killed people. I expect so. They shot at me. Everyone was watching and waiting and shooting. Twice I was hit: once in my right thigh; and once a bullet grazed my head just above my left ear. The hair has never grown back in the scar. That one was too close.

Now I spend my days out in the open. Give me flat green fields. I don’t like the taller-than-a-man corn and sunflowers. Sugar beets, tomatoes, cabbage, soybean—I okay with those fields. Corn, I especially don’t like, because of when they burn the field stubble. Plumes of black smoke on every horizon, and nearer, reminding me of the burning vehicles, barns, hay mounds and houses during the war.

Why do they do it? Why did we do it?

The dog works real good. It’s bred into them. This one’s been with me for almost eight years. Came out of my father’s dogs. Guelph is her name, when I must name her for other people. After the city in Canada where my sister and her family lives.

I must oil or wax a few door hinges, some squeaky floorboards, that one step, he thought while getting water for a cup of coffee. I’d rather be silent than disturb the neighbours, or to give them things to talk about.

“Alone in a place that could house a couple or a whole family...Why does he need so much space? Why didn’t he rent a single room somewhere else?”

Grey light filters through the small window set high in the east wall, too high to look out through unless I tilt my head back and look up. Clear glass window, then a frosted glass window, then a cobweb- and dust-coated screen. Not that there’s much of anything to see: no sky, but there’s a two-storey brick wall with cement mortar on the lower part, a near horizontal drainpipe heading toward the street, the top of a window with white- and peach-coloured curtains and trim the colour of dried blood. Almost exactly the same tint of paint used inside here on the gas-heated hot-water radiator and its pipes snaked across two white walls.

“What are his plans? What does he do? Does he have a job? So many people here don’t work.”

The weighted box placed against the second entrance’s inner door kept it shut. The wood-and-frosted-glass door, meant to be held shut by two pair of magnets that don’t touch, repeatedly banged open, or creaked in gusty winds during the night. Someday, if the bricklayer ever gets back to town from a job in a neighbouring country, he is supposed to close up the holes around the outer iron-frame-and-frosted-glass door welded to pins installed in the brick wall days before I moved in. Might be a wise plan. Today is the eve of Samhain. The nights have gotten cold enough for the landlord to put on the heat for a few hours in the evenings and mornings.

“I’ve heard strange music, mostly not our music, but never a television.”

I stepped outside, a small grocer’s bag of accumulated garbage in my hand and walk through the covered entryway to the cobblestone street to leave it for collection. There’s mostly yellow leaves everywhere under the trees, on sidewalk and street. A few mare’s tails stream dark grey against the high undersides of some clouds. There’s a few blue patches as well. Looks like it will be an okay day to walk my hill-climbing sore leg muscles along the much flatter riverside levees. I’d bike but the bike is gone. Others came while I was away and their need was greater than mine.

“Does he ever have visitors? I’ve never seen one.”

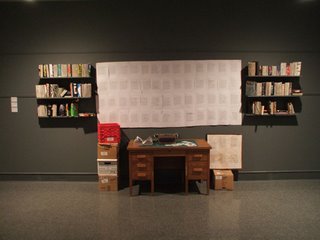

A small floor mat, or carpet, would be good for the entry—for safety against slipping when the tiles, or footwear, are wet. Plus a carpet for the livingroom. And more mats for the bathroom’s tile floor by the shower and sink. But connecting the clothes washer to the plumbing in the wall takes priority; then, maybe, installing a kitchen sink and countertop. A working light on the bare wires over the outside door would be useful at night. A finished floor in the second room—parquet laminate, ceramic tiles, or wall-to-wall carpet—is a must on the bare, not even painted, cement. The sheets of cardboard—some of them flattened cargo boxes—have to go! Art on the walls, not just flags in windows, and more furniture would improve the appearance of being settled, but not too much stuff on the walls. Bare might be better for calm or inspiration.

“He’s brought that dog around several times. I think it belongs to the woman that helped him rent the flat. She’s been there once or twice that I’ve seen. Maybe he needs help. Maybe he’s not all there in the head.”

How long I stay here, how long I’ll live, are anyone’s guesses, but these autumn days this is my shelter, my house, my home. The refrigerated cache and electric fire for my food are here. Sure, I forage across the fields, along the rivers, in the forests, over the mountains, but this lair, this Old World cave, den, base camp, roost, my current “wall with the hole in”...call it what you will, it holds the pillow, the bed where I now lay my head.

“His lights are on some nights, but other times it’s dark and completely silent for nights in a row, as long as a week. Imaging renting a place, then not even living there...”

My skeleton opens a door in a wall on an old roman road.